Published 14 September 2020 ● Last Updated on 17 August 2023

Have you ever walked down the aisle of a mega store with the best intentions to buy products that are sustainable? Have you read and re-read labels like biodegradable, eco and all-natural, and chosen these with confidence that the brand was environment friendly? Have you thrown away these items at their end-of-life with a warm sustainable feeling in your heart?

While I truly commend your efforts in choosing sustainable products that benefit the planet, I’m here to share a little more about these claims that will hopefully help us make better choices in our minimal impact journey.

What is greenwashing?

Greenwashing is a term coined in the 1980s by environmentalist Jay Westerveld to describe unsubstantiated or misleading claims about the environmental and ethical impact of a company’s products and services. These claims are meant to increase profits and reputation of the company without them channeling enough resources into truly making a difference. Back in the day of no internet, it was easy for consumers to believe these claims, but today we hold real consumer power in our hands to weed out these daring declarations and vote better with our wallet.

How can you spot greenwashing?

Curating from Terrachoice’s seven sins of greenwashing and examples from the University of Saskatchewan, here are a few of the top claims companies tend to make.

Watch for hidden trade-offs:

A high proportion of greenwashing claims fall into this category, where a company claims a product is green based on a very narrow set of attributes without taking into account other areas impacted by the same product. The green claim is usually so small that it does not offset the larger footprint of the product or make any environmental difference.

Examples:

- Devices like printers, copies and fax machines may focus on energy efficiency, but fail to mention if they contain hazardous materials, or if they are compatible with recycled paper or remanufactured toner cartridges.

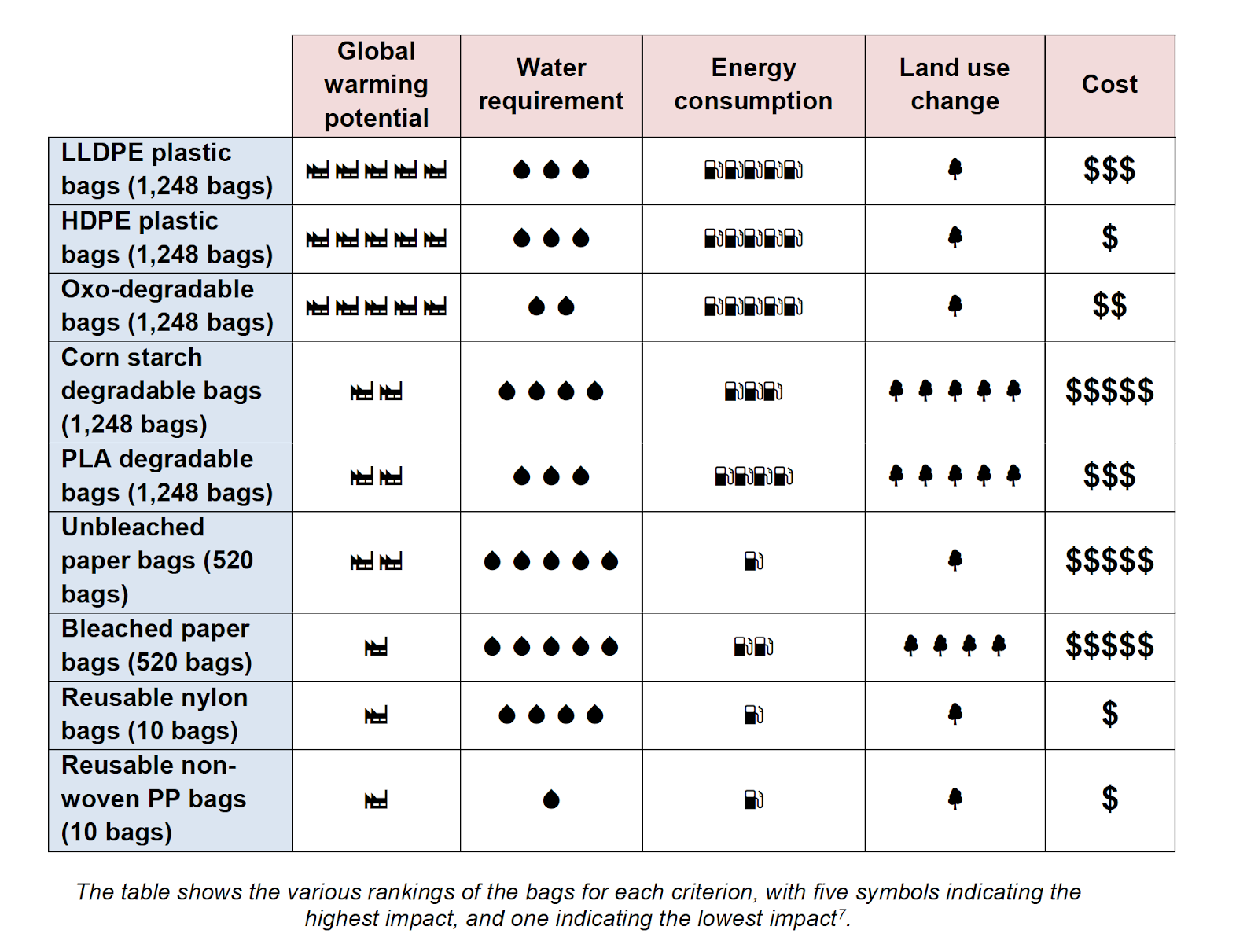

A product’s packaging might be labelled “made from recycled materials” without including any environmental impact of the product itself. - Plastics labelled “bio-based” and “bio-degradable” are common offenders in this category. While bio-based plastics are made from non-petroleum products like corn and bagasse, they have a significant impact on crop cultivation where food crops are phased out for crops that can be used to make plastic. As for bio-degradable plastics, they only degrade under very specific temperature and humidity conditions which are usually not communicated to the consumer – and hence, usually not followed through. In Singapore for instance, any bag – no matter what it is labelled – will end up in the incinerator if it is binned.

- A fashion company may claim that its clothing is made from sustainable or recycled materials, with no information about other chemicals used in the manufacturing process. After the collapse of the Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh in 2013 that took the lives of more than 1000 garment workers, the working conditions of those who make our clothes is one of the most important vectors in a company’s sustainability disclosure. Sadly, this aspect is often missing. In the words of Prada’s top model Arizona Muse who is championing sustainability in fashion, this is called intersectional environmentalism, where different aspects have to intersect to make a product truly good for the planet and its people.

Watch for claims with no proof:

From Terrachoice’s survey, a quarter of transgressions occur when a company uses extensive green language in its marketing which cannot be substantiated by easily available information to the consumer (either at the point of purchase or on the product website). An official sounding certification is sometimes included, but it takes a bit of work to verify its authenticity (see the next section for more information on how to spot a valid certification).

Examples:

- Small household appliances and light fixtures may claim to be energy efficient either without a certification label or one that might need more verification.

- Personal care products like shampoos may claim not to be tested on animals. Head over to the PETA website to confirm if indeed your preferred brand is as ‘cruelty free’ as it claims to be.

- Household paper products may claim to be made from post-consumer recycled content without any proof of what percentage of the entire product is manufactured this way. Certain paints are recently claiming an “air-purifying” property, for which there is no large-scale study or proof.

Watch for vagueness:

Using tricks of language again, these marketing claims play on poorly defined green claims, and sometimes may also use broad terms without specifying any details to help the consumer make an informed choice.

Examples:

- Terms like “chemical-free”, “non-toxic”, “all-natural” are debatable when no details are included about what exactly they mean. All living things are also made of chemicals, does that mean there are natural chemicals and synthetic ones, and if so which ones are okay? Harmful elements like arsenic and mercury are all-natural, does that mean there are harmful natural elements and safe ones? You see where I’m going with this? These claims are impossible to believe unless there is more information on what exactly they mean, preferably detailed on the product’s site clearly for consumers to read.

- Even if a product was proven “all-natural” and “organic”, there are many naturally occurring substances that produce toxic and allergic effect on us. Head to Environmental Working Group (EWG) database to confirm if the product you are planning to use is indeed free from known endocrine disrupters and carcinogens.

- “Green”, “environmentally-friendly” and “eco” are some of the most common terms in use to market products to the sustainably minded consumer. It is an immediate red flag to pause, question and confirm the details before proceeding.

Watch for irrelevance:

This occurs when a company makes a true environmental claim, but which is unconnected, unimportant or unhelpful to the consumer making a choice. It serves to catch the consumer’s eye and distract from the real issue at hand.

Examples:

- The most popular claim in use even today is “CFC-free”, but it is irrelevant since CFC has been banned the world over for years.

- Anything labelled biodegradable or compostable deserves a mention in this category specifically in the Singapore context. Since we incinerate all the waste we throw down our rubbish chutes, nothing will biodegrade or compost simply because of our specific waste disposal system. These labels are usually used on plastic items like bags and cutlery to prod consumers to spend a few extra bucks, but that’s the time to pause and reflect on the context and if it is relevant in our corner of the world.

- Did you know that in Singapore, claims of ‘hormone/antibiotic free meat’ are mere marketing gimmicks with hefty price tags for the products? The reality is that all meat imported into Singapore is required by SFA (Singapore Food Agency) to be free of artificial hormones and growth antibiotics.

What can you do to avoid greenwashing?

The legal ramifications and loss of reputation due to greenwashing are real threats for companies. While in-depth research into brands and companies before buying from them is quite difficult, here are a few tips you can use which can make greenwashing easier to spot:

- Do a simple search for “brand greenwashing”, and this should give you a starting point to see if the brand walks its talk.

- Look for concrete facts and numbers on their sustainability pages which track current and future targets, not flowery language that paints a pretty picture of being environmentally friendly.

- Look for goals with deadlines, this is a strong indication that sustainable development goals are part of the corporate strategy and are being tracked publicly if they are met or not.

- If a brand truthfully states that it hasn’t met a certain goal with a detailed explanation of why, this is more reason to believe that it is indeed trying.

- Each product is the result of a supply chain. Look for details about the manufacturing process, this should give you an indication if the company’s claims stem from a deep look at their entire business or not. This is usually detailed in a non-financial disclosure, but reporting across companies is not yet standardised. Watch this space for the brands you love, because the Singapore Exchange has made Sustainability Reports mandatory since 2016, and there are efforts underway to make these reports themselves standardised and more accessible to consumers.

- Leverage resources like the Ecolabel Index which lists hundreds of eco labels and their profiles, PETA’s site to check cruelty free claims, EWG’s site to confirm ingredient safety and SFA’s site for myth busters on country specific food claims.

Oh no, then should you stop aspiring to be eco-friendly?

No, definitely not. The problem is only in certain marketing murkiness which you can weed out with the information stated here, but there are definitely brands that are trying hard and doing well too.

- Shopping at local small businesses is a safe bet, and it gives you a chance to personally talk to them about their sustainability process. We would include food and meat choices In this category – where you have a chance to see ethics (or lack of) for yourself! Indeed, you may find businesses that meet sustainability criterion even when they do not have the money to pay for a certificate on their label.

- Even for your favourite big brand products, ask them pointed questions and request data on their social media platforms. In today’s world where brand image is worth millions this will get you the information you need, and you might find that other consumers also join you in this quest.

- In some cases, you may find that certain culprits with irrelevant claims may still be a better choice – for example, cutlery made from discarded/fallen plant products by farmers in developing countries use fewer resources and benefit more people than ones made from plastic (made from petroleum products) or bio-based (made from plants grown specifically for such production). Win-win on the production side, even if our disposal system will not compost it at its end-of-life.

So there is hope, after all. If more consumers like us walking down aisles and reading labels ask more questions, companies might finally listen to the rising chorus of voices demanding a more truthful and easy to understand path to sustainable consumption.

Related Articles

Eco inventions | 7 unusual products that are planet-friendly

0 Comments