Published 22 June 2023 ● Last Updated on 11 August 2023

As the world continues to come to terms with climate change and its effect on our lives, it is essential that adequate investment and resources are aligned with the net zero pathway. To demystify the concept of and the path to Net Zero, this article focuses on 4 key pillars needed for its realisation and where we are in that journey. This is part 2 of a two-part series.

The 4 pillars that are necessary to achieve the goal to get to Net Zero are:

A. Energy transition and renewable energy

There is an urgent need to make that shift from traditional sources of energy. In May 2022, at the ‘ Launch of the World Meteorological Organization’s State of the Global Climate 2021 Report’, UN Secretary-General António Guterres outlined the critical actions the world needs to prioritise to transform our energy systems and speed up the shift to renewable energy, asserting that – “without renewables, there can be no future.”

- Make renewable energy technology a global public good

It is imperative that renewable energy technology is available to all, and not just the wealthy. This will be essential to remove roadblocks to knowledge sharing and technological transfer, including intellectual property rights barriers.

- Improve global access to components and raw materials

The concentration of renewable energy technology and raw materials within a few countries will need to be addressed. This is possible if coordinated efforts are undertaken by stakeholders to build supply chains and invest in training, research, and technological innovation. The goal is to level the playing field for renewable energy technologies.

Along with global cooperation and coordination, streamlining domestic policy frameworks is critical so as to fast-track renewable energy projects and private sector investments. Technology, capacity, and funds for renewable energy transition exist, but there needs to be policies and processes in place to reduce market risk and incentivise investments. Nationally Determined Contributions, countries’ individual climate action plans to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts, must set 1.5C aligned renewable energy targets.

- Shift energy subsidies from fossil fuels toward vulnerable communities

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), about $5.9 trillion was spent on subsidising the fossil fuel industry in 2020. This includes explicit subsidies, tax breaks, and health & environmental damages that are not priced into the cost of fossil fuels.

Conversely, investments in renewables should be tripled to a minimum of $4 trillion a year. This includes investments in technology and infrastructure – to allow us to reach net-zero emissions between 2050 and 2060. If this is achieved, as per IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency), a reduction of pollution and climate impact alone could save the world up to $4.2 trillion per year by 2030.

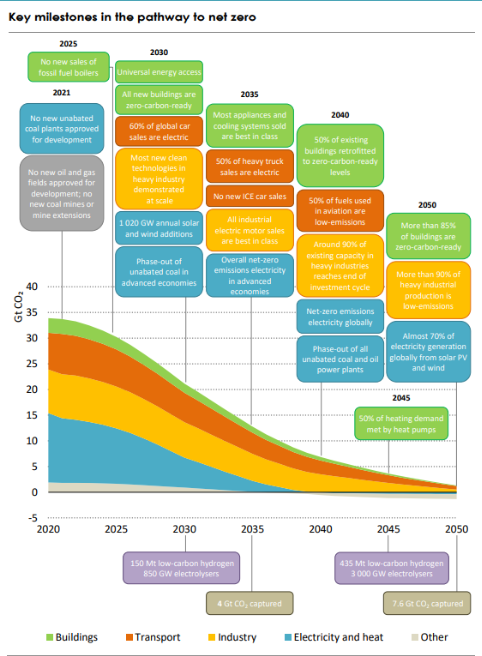

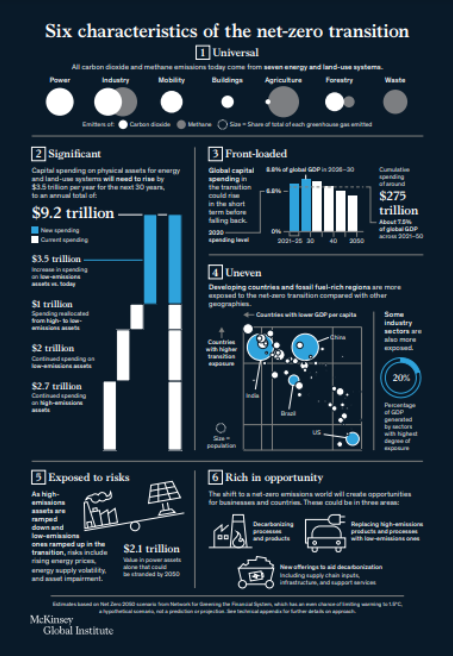

B. Decarbonising industry, transport, and buildings

The path to net‐zero emissions is narrow: staying on it requires the immediate and massive deployment of all available clean and efficient energy technologies. Decarbonising also requires a big investment, innovation, infrastructure, and technology deployment alongside skillful policy design & implementation of international cooperation and efforts across many other areas.

C. Harnessing technology

Carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) refers to a suite of technologies that play a diverse role in meeting global energy and climate goals. It involves the capture of CO2 from large point sources, such as fossil fuel or biomass-based power generation and industrial facilities, or from the atmosphere directly. The captured CO2 is compressed and transported to be used in a range of applications, or injected into deep geological formations, like depleted oil and gas reservoirs or saline aquifers that trap the CO2 for permanent storage.

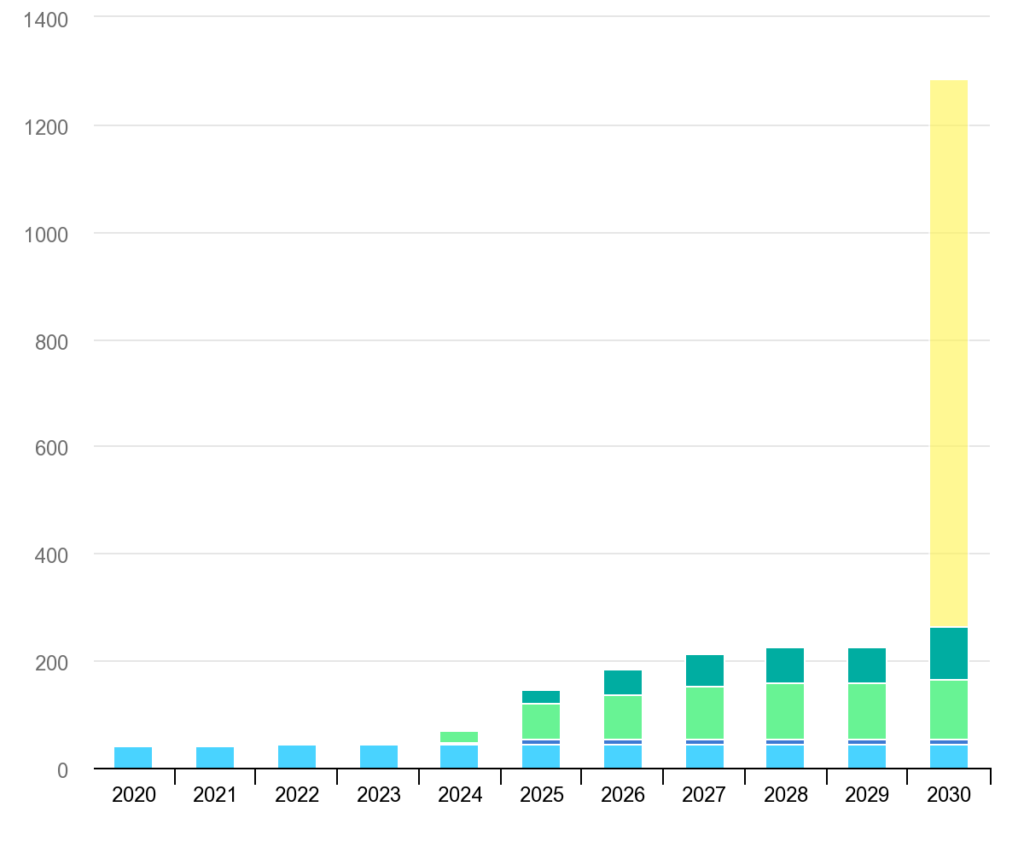

Currently, there are about 35 commercial facilities applying CCUS to industrial processes, fuel transformation, and power generation, with a total annual capture capacity of almost 45 Mt CO2. While CCUS deployment has fallen behind expectations, there has been an increase in recent years, with around 300 projects in various stages of development. Project developers have also made an ambitious announcement of adding over 200 new capture facilities to be operating by 2030, capturing over 220 Mt CO2 per year.

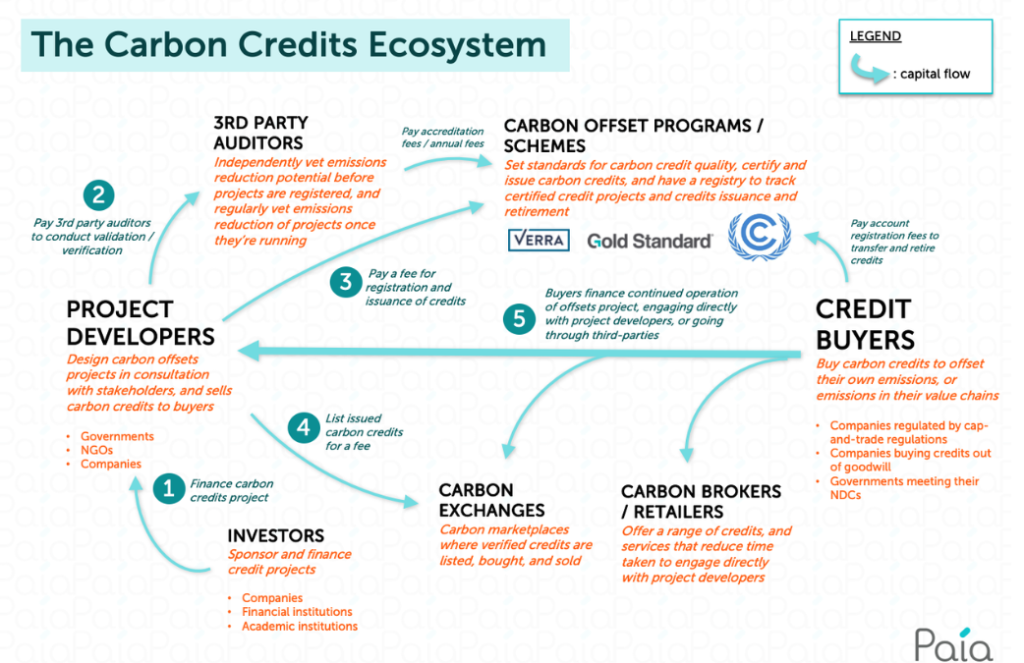

D. Carbon offset / Credit

Carbon offset and carbon offset credit are used interchangeably, though they can mean slightly different things. Carbon offset broadly refers to a reduction in Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) or an increase in carbon storage through land restoration or tree planting etc, that is used to compensate for emissions that occur elsewhere.

A carbon offset credit is a transferable instrument certified by governments or independent certification bodies that represents an emission reduction of one metric tonne of CO2, or an equivalent amount of other GHGs. The purchaser of an offset credit can use it to claim reduction towards their own GHG reduction goals. Essentially, offset credits are used to convey a net climate benefit from the seller to the buyer. This works because GHGs mix globally in the atmosphere, so it does not matter where exactly they are reduced or who is contributing to this reduction.

4 types of carbon offset projects are currently in place.

1. Forestry and conservation

Reforestation and conservation are popular offsetting schemes. Credits are created based on either the carbon captured by new trees or the carbon not released through protecting old trees. Forestry projects are not the cheapest offset option, but they are often chosen for their many benefits beyond carbon savings like protecting ecosystems and wildlife.

There were some grey areas in forestry offsetting in the past when it was difficult to distinguish how much carbon is being reduced through forestry projects. Thanks to emerging technologies, methods of sustainable reforestation and estimations of the benefits have greatly improved these days.

2. Renewable energy

Renewable energy offsets go toward building or maintaining solar, wind, or hydro sites across the world. Companies purchasing these credits boost the amount of renewable energy on the grid, creating jobs, decreasing reliance on fossil fuels, and bolstering the sector’s global growth by investing in these projects. In addition, the profits from selling carbon credits are often fed back into local community projects. To achieve Net Zero Emissions by 2030, renewable energy use must increase at an annual rate of about 13% from 2023 to 2030, twice as much as over the past 5 years.

3. Community projects

These projects help introduce energy-efficient methods or technology to undeveloped communities around the world. Notably, carbon credits are one of the many benefits of projects like these. Other positive outcomes are improved sustainability in the region, community empowerment, and enabling independence that uplifts them out of poverty. Basically, projects that were typically philanthropic can now provide organisations with additional benefits like carbon credits.

4. Waste to energy

A waste-to-energy project mostly involves capturing methane and converting it into electricity. Sometimes this means capturing landfill gas, or on smaller scales, human or agricultural waste. In other words, waste-to-energy projects can impact communities in the same way efficient stoves or clean water can.

Carbon offset can be of 2 types – Carbon avoidance, those offsets that reduce emissions from existing or future operations, and Carbon removal, those that remove existing carbon in the atmosphere.

Carbon avoidance projects commonly include renewable energy projects that enable the replacement of carbon-intensive fuel-burning processes, such as wind farms, biomass energy, hydroelectric dams, or biogas digesters.

Carbon removal projects include both nature-based solutions such as mangrove restoration, where new trees planted sequester carbon from the surrounding air, and technological solutions, such as enhanced mineralisation and direct air capture.

On one hand, carbon offsets hold promise to accelerate decarbonisation and deliver other benefits globally, channeling funds to projects that may otherwise have lacked the resources to operate. However, offsets have not always lived up to their credibility, resulting in accusations of greenwashing.

Net zero – A report card

Where do we stand in our journey towards the goal? A new climate action tracker tool, Speed & Scale Tracker shows achievements and setbacks on global goals to cut emissions to net zero by 2050.

As per this report, there are some commendable wins:

1. Strong momentum in the electric vehicle sector

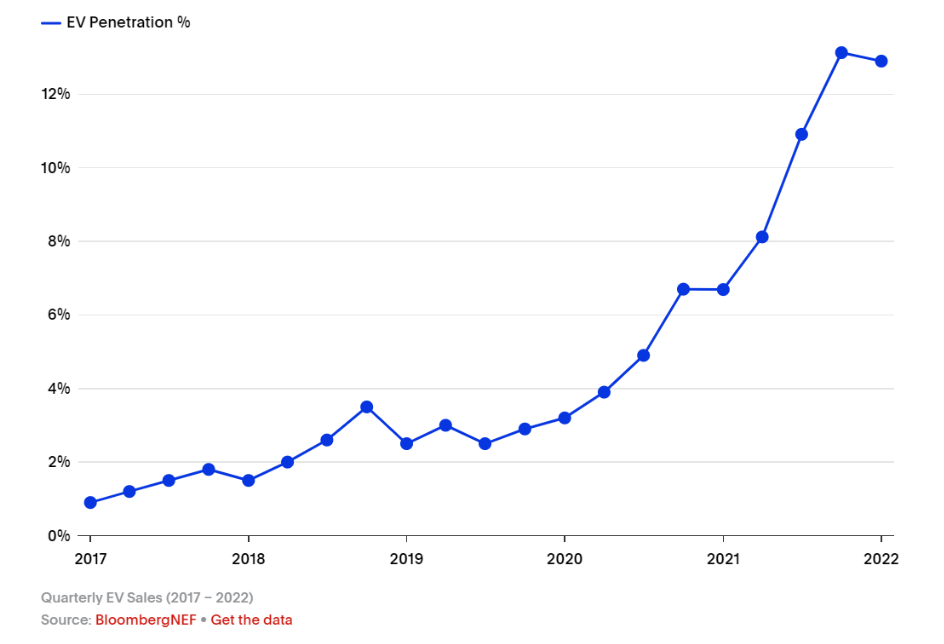

Sales of electric vehicles have more than doubled from 4% in 2020 to nearly 9% in 2021. To be on track for net zero, this share must reach 50% of global auto sales by 2030.

2. Electricity generation is on track

The world is making strong progress on the electricity generation front, with 39% in 2020 coming from zero-emission sources. The goal is for half of the electricity generated globally to come from zero-emissions sources by 2025, rising to 90% by 2035.

3. Increased investment in climate ventures

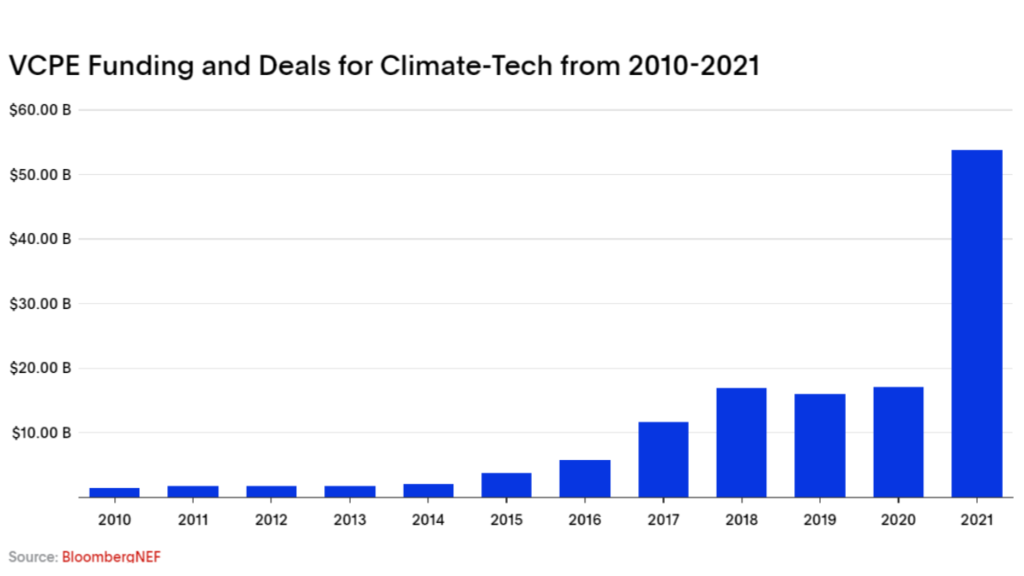

Just one goal in the tracker has already been achieved. This is to grow investment into climate technology start-up companies in the United States to $50 billion a year. This was achieved in 2021, when investment levels reached $53.7 billion, up from $17 billion in 2020. More than half of this funding went to transport solutions.

There are a few unfortunate losses too. They are:

1. Lack of adequate ocean protection

Only 8% of the Earth’s oceans are currently protected against the goal of protecting at least 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, and 50% by 2050. In particular, the practice of deep-sea bottom trawling in the commercial fishing industry needs to end, because this method of dragging heavily weighted nets across the sea floor releases CO2 into the seawater and thus the atmosphere.

2. Dependency on coal and gas

345 new coal plants and 438 new gas plants are currently under construction across the globe. This is a huge area of concern because the world has to stop building new coal and gas plants immediately to meet net-zero requirements. In fact, existing coal and gas plants must have zero emissions or be closed by 2025 and 2035 to reach the net zero goal.

3. Not enough green diets

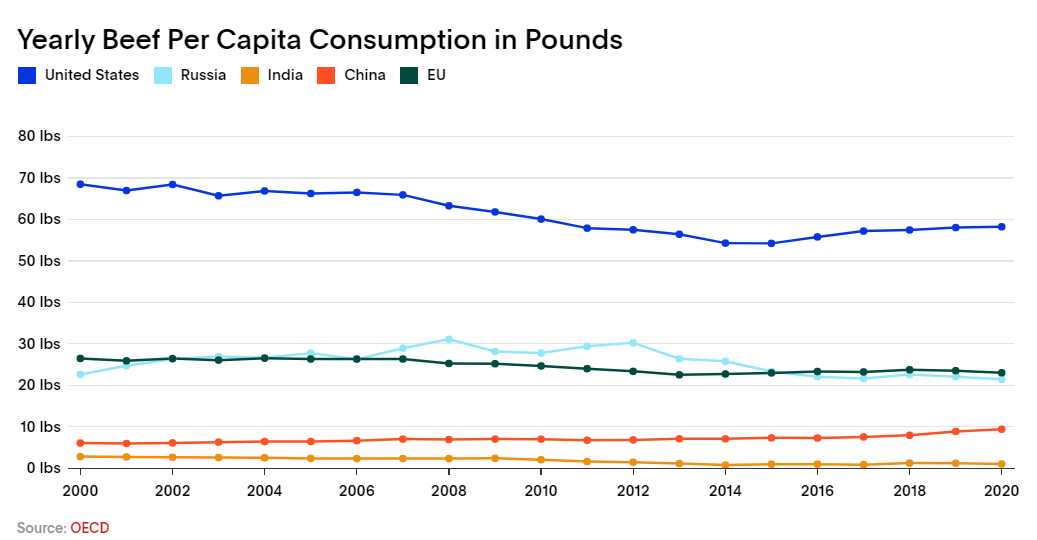

In order to cut emissions from livestock, the world needs to eat a quarter less beef and dairy by 2030, and 50% less by 2050. This goal is currently off track with consumption increasing instead.

4. Missing forest protection

In 2021 a total of 3.75m hectares of forest were lost because of human action. This means every six seconds, a forest area the size of a football field is lost. A commitment to end deforestation by 2030 was made by 141 countries at the COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November 2021.

5. Seal the steel

Steelmakers need to halve emissions from the steel-making process by 2030, rising to a 90% cut in emissions by 2040. The steel industry currently generates 1.9 metric tons of CO2 per metric ton of steel produced. It is the single biggest industrial source of emissions, at 4 gigatons.

6. Heavy industries

Along with steel, the top global emitters are aluminum, aviation, chemicals, concrete, shipping, steel, and trucking.

Falling behind

A report by Accenture highlights that while more than one-third (34%) of the world’s largest companies were committed to Net Zero by November 2022, it expects that almost 93% will fail to achieve their goals if they don’t double the pace of emissions reduction by 2030.

Accelerating Global Companies toward Net Zero by 2050 finds that growing energy price inflation and supply insecurity is pushing commitments out of reach, even as more companies in every region are setting clear and publicly visible decarbonisation goals, with a record rise in the number of corporate targets validated by the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) this year alone.

What next?

The global political economic system, be it capitalist, socialist, or communist, must achieve the rapid decarbonisation necessary to avoid the worst outcomes of the climate crisis. This would include strong government action in taxing carbon, investing in extensive networks of high-speed trains powered by electricity, extensive tree planting, incentivising low-carbon technologies, preventing food waste-related methane emissions, everything produces enormous climate problems, ‘carbon smart’ farming techniques that store carbon in the soil.

Decarbonising the economy can be a net gain in jobs and prosperity, especially in the long run. More people work in the solar and wind industries than in coal or other fossil fuel extraction.

But we can’t sugarcoat the pain of the near-term transition. People will need to drive less, pay the actual cost in carbon emissions for suburban or urban lifestyles, and require assistance moving out of fossil fuel jobs. Ultimately, political will and popular support are required to reverse climate change.

0 Comments