Published 14 June 2023 ● Last Updated on 11 August 2023

By now, there is no doubt that climate change is an imminent threat and needs to be addressed. You may have heard of the IPCC report, the Paris Climate Agreement, the landmark COP meetings, Carbon Offsets, and Carbon Capture. In a world requiring urgent climate action, we see the need to decode the ubiquitous term known as “Net Zero”. This is Part 1 of a two-part series.

The concept of Net Zero emissions or Net Zero refers to the point in time when all emissions caused by human activity are negated by the removal of carbon from the atmosphere.

For an effective Net Zero score, the balance between emissions and removal has to be permanent! In order to achieve this, human emissions should be reduced to as close to zero as possible, while the removed greenhouse gasses should never return to the atmosphere. The latter can be achieved through natural approaches like restoring forests, or through technologies like direct air capture and storage (DACS), which scrubs carbon directly from the atmosphere.

Back to the basics

Recognising the pressing need to put an end to emissions, in 2015, the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) adopted the Paris Agreement in Paris, France, on 12 December 2015. As per this Agreement, 197 countries agreed to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, ideally to 1.5 degrees C. Global climate impacts that are already unfolding under the current 1.1 degrees C of warming — from melting ice to devastating heat waves and more intense storms — show the urgency of minimising temperature increase.

Why must we chase Net Zero?

Global warming is proportional to cumulative emissions. This means the planet will keep heating as long as global emissions are more than zero, resulting in damage to the planet.

Science suggests that limiting warming to 1.5 °C depends on CO2 emissions reaching net zero between 2050 and 2060. Reaching net zero earlier avoids a risk of temporarily “overshooting,” or exceeding 1.5 °C. Reaching net zero later almost guarantees surpassing 1.5 °C for some time before global temperature can be reduced back to safer limits through carbon removal.

Critically, the sooner emissions peak, and the lower they are at that point, the more realistic achieving net zero becomes. This would also create less reliance on carbon removal in the second half of the century.

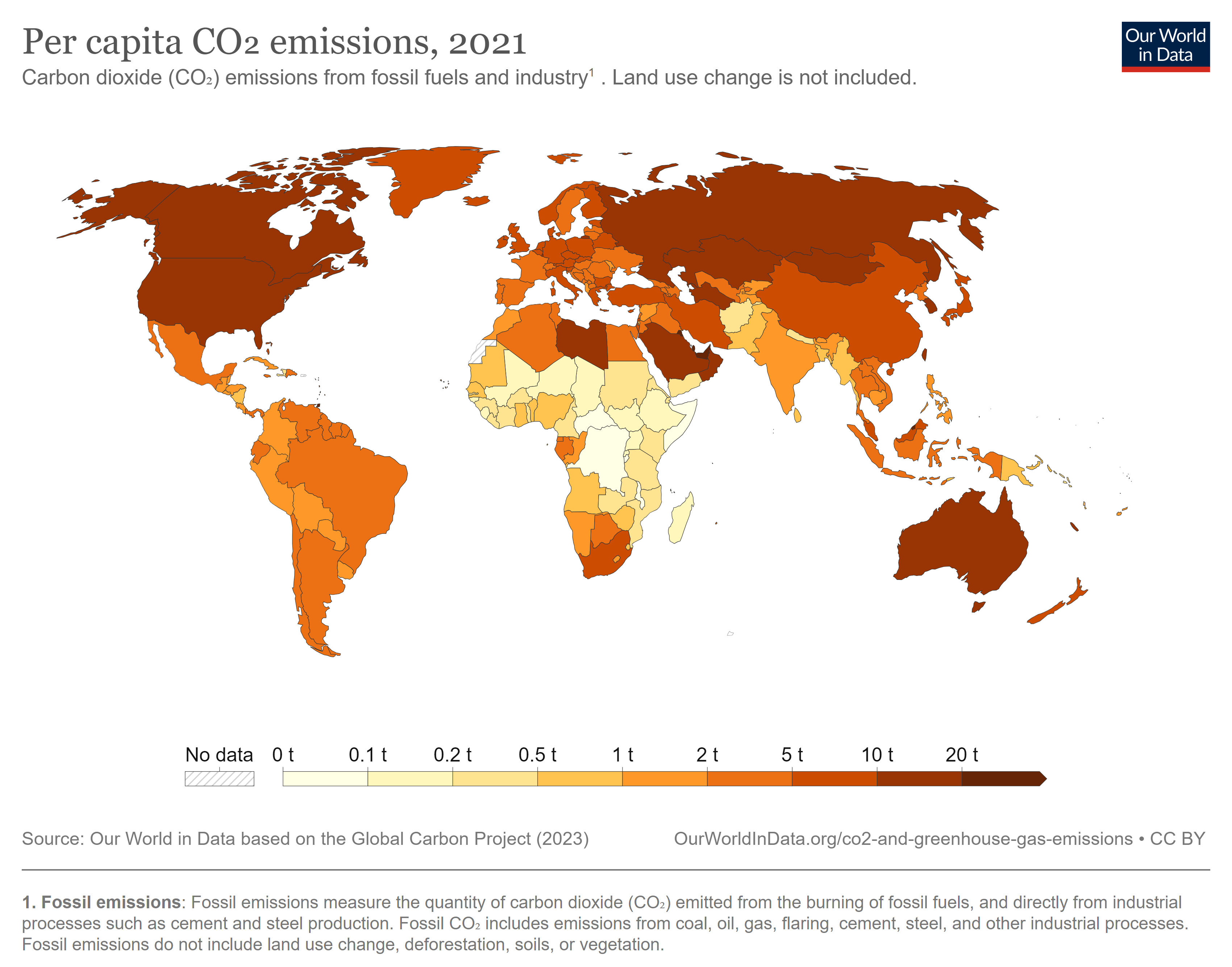

This does not suggest that all countries need to reach net-zero emissions at the same time. The chances of limiting warming to 1.5 °C depend significantly on how soon the highest emitters reach net zero. Equity-related considerations — including responsibility for past emissions, equality in per-capita emissions, and capacity to act — also suggest earlier dates for wealthier, higher-emitting countries.

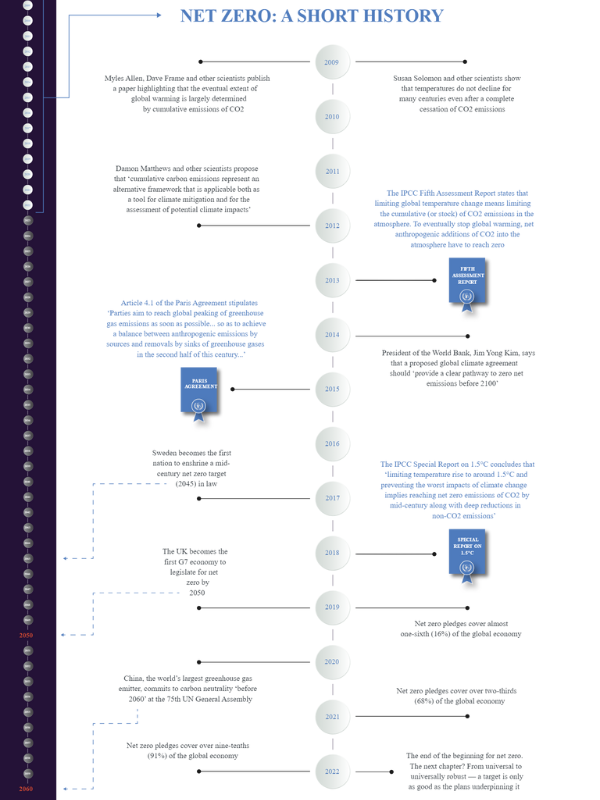

A Brief History of Net Zero

Collective Commitment towards Net Zero

A growing coalition of countries, cities, businesses, and other institutions are pledging to get to Net Zero emissions. More than 70 countries, including the biggest polluters – China, the United States, and the European Union have set a net-zero target, covering about 76% of global emissions. More than 3,000 businesses and financial institutions are working to reduce their emissions in line with climate science, and more than 1000 cities, over 1000 educational institutions, and over 400 financial institutions have joined the Race to Zero, pledging to take rigorous, immediate action to halve global emissions by 2030.

The top seven emitters (China, the United States of America, India, the European Union, Indonesia, the Russian Federation, and Brazil) accounted for about half of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. The Group of 20 (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union) are responsible for about 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition to countries, organisations globally have made their own individual Net Zero pledges. They are guided by voluntary schemes, like Race to Zero, the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance, and the Science-based Target Initiative. The progress made is measured by frameworks such as CDP and the Transition Pathway Initiative. Source: UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2022

Are we on track to reach Net Zero by 2050?

A report issued in 2021 by a U.N. panel warned that the impact of climate change is severe and widespread; while there is still a chance to limit warming, some of its impacts will continue to be felt for centuries. Calling this report a “code red,” the U.N. Secretary-General, António Guterres said, “The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse‑gas emissions from fossil-fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.”

Governments though are falling short of the commitments made. In order to toe the line of the agreement, the biggest emitters have to significantly strengthen their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and take urgent and significant steps toward reducing emissions. The Glasgow Climate Pact called on all countries to revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their NDCs by the end of 2022, but only 24 new or updated climate plans were submitted by September 2022.

So, who have been the biggest emitters?

COUNTRIES

To limit warming below 1.5°C and prevent irreversible damage from climate change, the world collectively should reduce carbon emissions by 45% from the 2010 level by 2030. The sharpest cuts are to be made by the biggest emitters. However, according to the most recent report, countries’ current plans to cut emissions are nowhere near sufficient, totalling just about a 1% reduction in global emissions by 20301% reduction in global emissions by 2030.

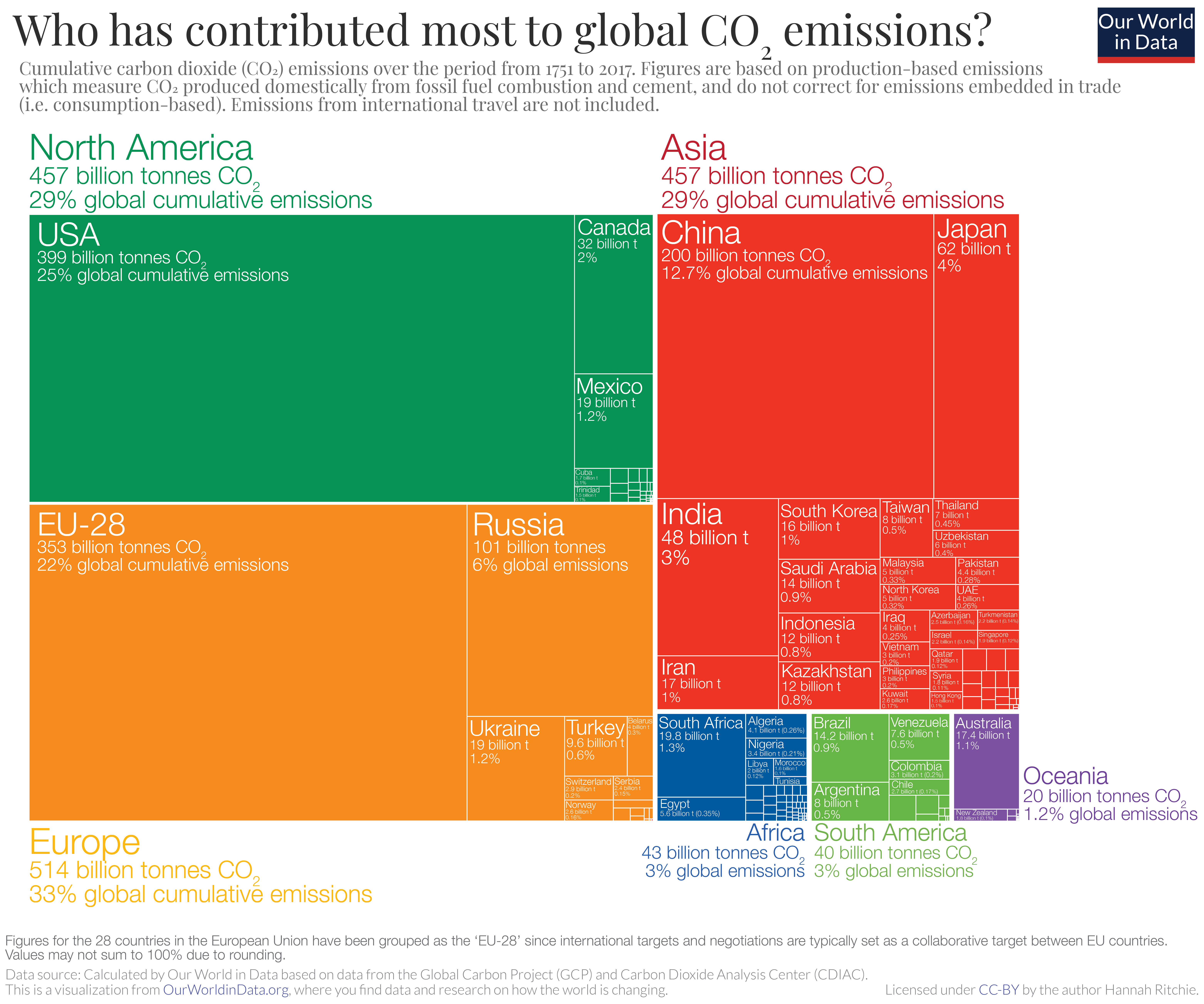

Historically developed nations have contributed to more emissions than all other countries in the world. The United States has emitted more CO2 than any other country to date. It has in fact emitted around 400 billion tonnes since 1751 and is responsible for 25% of historical emissions. This is twice more than China, the world’s second-largest emitter. The European Union (EU-28) is also a large historical contributor at 22%.

SECTORS

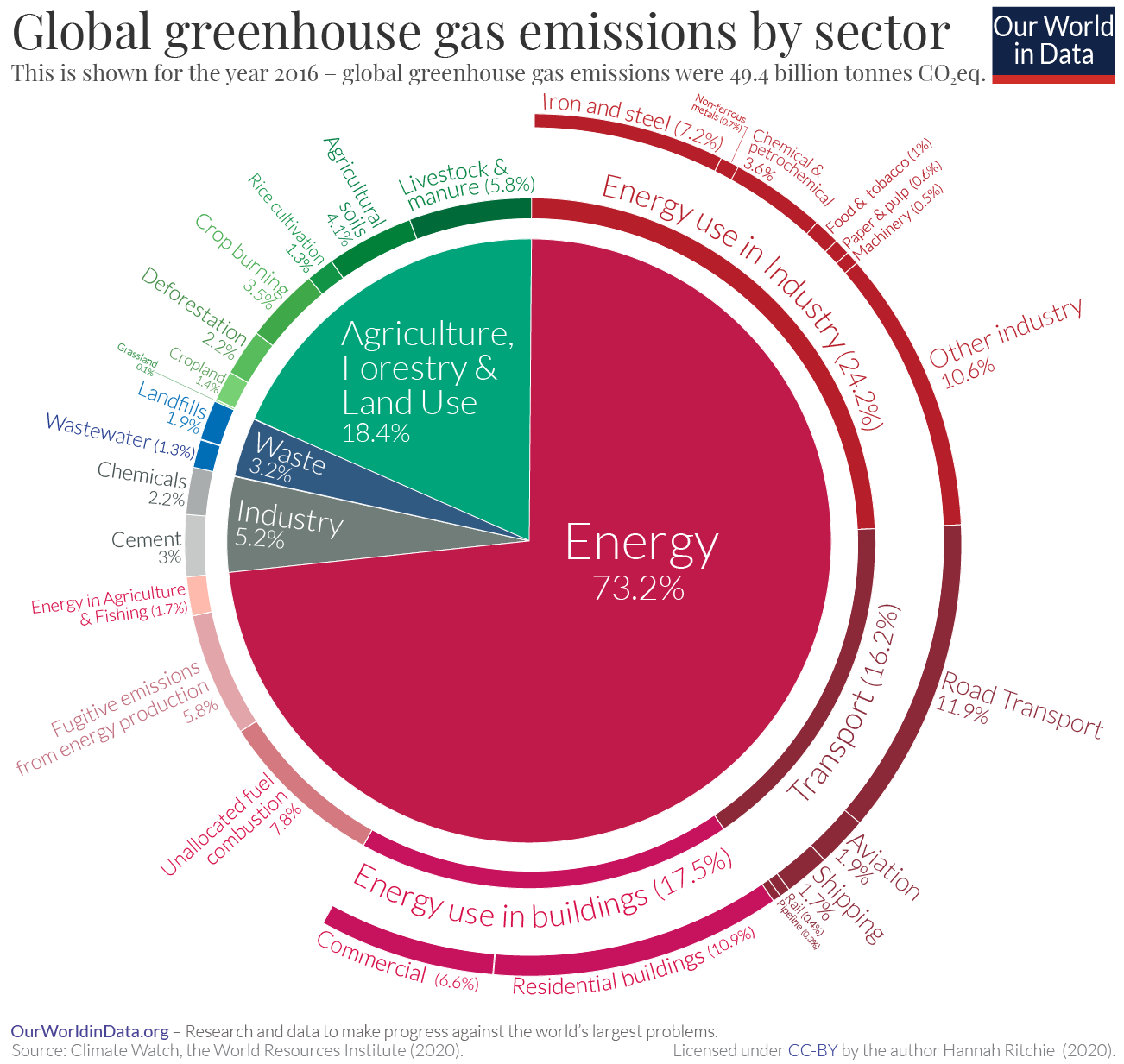

Regarding economic activity, the most prolific GHG emissions- a whopping 75%- happen due to energy use. 18% can be attributed to agriculture, forestry, and other land use, and the remaining comes from industry and waste.

In the next part of the Net Zero series, we will dive deep into the Path towards Net Zero and take stock of where countries and corporations stand vis a vis their commitments.

0 Comments